Wages are consistently identified as a critical factor in recruiting, retaining, and supporting workers within the homelessness support sector. However, non-profits within our support sector must also stretch their finite grant funding as far as they can to maximize the number of vulnerable individuals supported by their programs. Raising wages across the sector will require a commitment to a new balance of resources shared across employer organizations as well as their grant writers and the funder organizations. This resource is intended to advance discussions related to this goal, and links to external resources that support the adoption of a $25 target wage within new grant applications and program renewals in the local sector (and, arguably, across communities). This target, above both the minimum wage and living wage rates, is in line with local evidence on cost of living and the overall objective of recruiting and retaining a strong, talented sector workforce.

- A PDF version of the below is also available, KHRC – A Case for a 25 Dollar Target Sector Wage (Nov 22 2021)

Feedback and questions can be directed to: ask.khrc@ubc.ca

A Resource for Discussion, Advocacy, and to Inform Grant Applications

The Context: Wages, Burnout, and Turnover

Earlier this year, Hub Solutions issued the results of a mixed-methods research project (Understanding the Needs of Workers in the Homelessness Support Sector – 2021) based on a rapid literature review, a review of job advertisements for positions in the sector, a cross-sectional national survey of frontline staff, and interviews with Executive Directors of homeless serving organizations. They identify that “burnout, inadequate wages, and availability of material resources and benefits were dominant factors influencing precarious employment, and employee retention and turnover in the sector” (p.4). EDs highlighted that frontline workers leave their jobs after short terms of employment, particularly those in shelters, outreach, and case management positions, with some specifying that the average length of staff between 12 and 18 months (p.55). The authors suggest that future research explore “how sustainable wage enhancements can be implemented for frontline staff in the sector to address issues including precarious employment, employee retention, and turnover” (p.6).

A University of Calgary study involving 472 front-line homeless shelter workers (PTSD Symptoms, Vicarious Traumatization, and Burnout in Front Line Workers in the Homeless Sector, 2019) identified that 71% of respondents were earning less than $50,000 annually, and 51% had 2 years of post-secondary education or less. In a subsequent discussion with The Star, an ED at a Drop-In Centre identified that:

“…these roles need higher salaries to ensure workers have enough experience or education for the job… Front-line work is not entry-level work, even though it’s perceived that way and funded that way. It takes a tremendous amount of skill to deal with situations effectively and in the moment…”

Similar research with emergency shelter staff in BC (Emergency Shelters: Staff Training, Retention, and Burnout – 2019) highlighted that interviewees “generally perceived training to be a ‘secondary issue’ insofar as retention and burnout were concerned, and were unanimous that the greatest cause of retention and burnout issues within their organization was the low wages they were able to pay their staff” (p.15) – that is to say it was recognized as an important topic, but “an areas that has already received significant attention, especially in comparison to other issues which may be more difficult to address such as the wages available to staff” (p.12). Research from Edmonton’s homeless sector (Burnout and PTSD in Workers in the Homeless Sector in Edmonton, 2016) previously identified that “poor pay, limited resources for training, and a lack of opportunity for promotion lead to high rates of emotional exhaustion and motivation to leave their jobs” (p.10).

If the support sector workforce isn’t empowered to fully meet their own basic needs, is it reasonable to expect that they can be fully present and best equipped to support the basic needs of others?

Turnover from departures and short-term absences from burnout both result in both economic costs for employers in the form on training and overtime, respectively, as well as service disruptions for vulnerable clients. If these challenges are widely experienced at a sector level, this can also result in an overall reduction in the collective institutional knowledge of a complex web of supports.

The Impact on Clients

Research in various caring professions have highlighted the direct correlations between low wages, high turnover and the quality of care and services that are provided to clients. Castle & Engberg’s 2005 article used multivariate analysis to tie decreases in quality of care to increases in turnover across various nursing professions, with Antwi & Bowblis’ 2018 paper on care in nursing homes similarly finding evidence of lower quality services and possibly increased client mortality. Hussein’s 2017 report further highlights the impact of low wages and working conditions on stress, and notes the associated impacts on both workers and clients served in the English adult social care system. And additional research has highlighted how “poor pay and benefits threaten the delivery” of high-quality preschool services in the US, to the detriment of societal wellbeing (Barnett, 2016).

Lower wages, gaps in training, and gaps in overall staff supports can impact the levels, capacity, and quality of service delivered, which inevitably result in people experiencing homelessness not having their needs met and not being able to access resources. This overall prolongs their experiences in homelessness, poverty, and trauma. This is plausibly more acutely impactful in teams such as outreach services, where clients may have very limited contact points to the sector, may use those contacts to access a variety of vital and urgent services, and who may be known to the sector exclusively though recognition. The 2019 report on Emergency Shelters: Staff Training, Retention, and Burnout highlighted that “high staff turnover and a low rate of staff retention… has numerous implications for the sector, and the quality of service provided” (p.9), noting:

“…if an organization has a low staff retention, a greater proportion of resources will have to be directed towards attracting, hiring and training new staff, rather than on delivering its primary service. Additionally, low staff retention acts as a positive feedback system to exacerbate the existing problems leading to low retention, such as burnout. Low staff retention creates a gap of experience in the work environment and increases the workload to be distributed amongst the remaining staff. This increased workload may entail an increase in responsibility, stress, length of shifts, and a decrease in organizational support. Exacerbated by the difficult and confronting nature of frontline shelter work, these factors significantly increase the risk of burnout.” (p.9)

While wages are not the sole contributing factor to retention – whose causes are noted to be interconnected and need to be addressed holistically – “if shelter staff feel they are being underpaid, or that they could earn significantly more economic remuneration elsewhere, then they will be far less motivated to stay in their current role – especially if their cost of living is very high where they currently live and work” (p.9).

The Limits of a Living Wage

The response to concerns of affordability is often to adopt a living wage, a threshold higher than a minimum wage to reflect the cost of living. The Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives “Working for a Living Wage” report’s definition is “the amount needed for a family of four with each of two parents working full-time at this hourly rate to pay for necessities, support the healthy development of their children, escape severe financial stress and participate in the social, civic and cultural lives of their communities” (p.2), or a “bare bones budget” (p.3). For example, the 2021 living wage for Metro Vancouver was estimated at $20.52/hour, $16.71/hour in Kamloops, $19.56/hour in Nelson, etc. (see Living Wage for Families BC for more info, or their 2021 Update Report for Vancouver). The updated figures were almost all higher than the living wages for 2019, with the exception of Trail which experienced a decrease in the living wage threshold. Kelowna was added to the community list, with an estimated living wage in 2021 of $18.49/hour, as well as Penticton at $18.55/hour.

This minimum livable threshold is often met for a variety of sector roles, federally (see Statistics Canada’s “profile of workers in the homelessness support sector”, 2019), provincially (see, e.g. the April 2021 wage grids from the Community Social Services Employers’ Association of BC), and also by the wage range observed locally in the Okanagan through the Complex Needs Advocacy Paper (p.22). However, this minimum is arguably not a sustainable target given both the evidence presented above, as well as the nature of these assessments – Living Wage Canada notes the following important caveats for their calculations:

While the methodology accounts for a range of costs, taxes and benefits experienced by a family, it does not account for:

-

-

- Credit card, loan or other debt/interest payments

- Savings for retirement

- Owning a home

- Savings for children’s future education

- Anything beyond minimal recreation, entertainment and holidays

- Costs of caring for a disabled, seriously ill, or elderly family member

- Anything other than the smallest cushion for emergencies or hard times

-

Given this context, the lowest survivable living wage is unlikely to retain staff if higher paying options are available. It is also unlikely to attract trained staff if the amount in insufficient to cover the additional cost of student loans in pursuit of that education.

This point has been identified locally in the context of the Okanagan’s support sector. The Complex Needs Advocacy Paper (July 2021) overviews the pay rates within local supportive housing projects (which already typically exceed the local living wage estimate) also noted the ongoing challenges:

“The wage for these positions is in the range of $19.50-$24.50 per hour, and these positions are often filled by individuals with high school degree or perhaps a human services diploma; and the career trajectory and related compensation is such that it discourages those with deeper qualifications and skills from making a career choice in this area. Individuals who have qualifications don’t stay in these positions for long and will move on to higher paying clinical positions that usually have more standard hours. Local service providers observe compounding factors of high stress and burnout as contributing to high rates of staff turnover in supportive housing units and shelters (and the sector in general).” (p.22)

The housing challenges facing New York’s homelessness sector workers were highlighted earlier this year by the New York Times (April 2021):

“Many employees of New York’s homeless shelters are themselves in precarious economic situations, taking on multiple jobs, working overtime and struggling to find their own homes… Though they typically earn more than the city’s $15-an-hour minimum wage, finding housing is still a stretch when the median rent for an apartment in New York is roughly $2,500 a month…”

The instability of survival wage ranges was further supported by the 2019 Regional Housing Needs Assessment in the Central Okanagan. Based on their analysis, they concluded that “renters earning $51,948 or more annually can afford a one-bedroom apartment in Kelowna” (p.79). That is equivalent to an employee working 40 hours weekly, 52 weeks per year at an hourly rate of approximately $24.98.

Renters earning less than this amount are either forced to either devote over 30% of their income to maintain their housing, or possibly to seek alternative arrangements that might be unsuitable to their situation, both of which are criteria for core housing need (per CMHC). As is the case for the vulnerable clients they serve, sector staff can accordingly be placed at risk for financial instability, housing precarity, or other serious situations such as experiences of domestic violence (see the recent Pan-Canadian Women’s Housing & Homelessness Survey, 2021, for a discussion of how individuals can be pushed to remain in unhealthy or violent relationships for housing, or this Vice report from 2016).

These challenges have likely continued through COVID-19. While BC’s Temporary Pandemic Pay program did provide funding for a wage top-up to employees of provincially funded organizations in health, social services and corrections who are delivering frontline services, it was limited to the 16-week period of March 15th through July 4th of 2020. Meanwhile, waves of infections and associated challenges and risks in maintaining services have continued. The Hub Solutions Report on worker needs flagged that Executive Directors indicated that “continuing to perform complex work with a high-risk population during the pandemic has been mentally exhausting for many of their staff” (p.5). Burnout has been observed across frontline roles in the past two years, as have associated risks for both personal wellbeing and care (see Galanis et al., 2021, for a systematic review on the conditions within nursing). In a 2021 policy brief produced by CAMH and the Mental Health Commission of Canada – COVID-19, Mental Wellness, and the Homelessness Workforce – they note that over half of participants in an online survey reported moderate levels of burnout (59.7%, p.4). The report goes on to recommend an extension of “improvements made during COVID-19 to pay and benefits, including hazard pay and sick leave” (p.1), in addition to a number of other recommendations for mental health supports and a prioritization of the sector for resources as the pandemic continues.

Actioning a $25 Target Wage through Shared Awareness and Future Grants

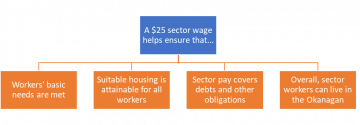

Overall, the evidence supports an increase in wages across the support sector. Locally, reporting on cost of living – as well as noted challenges of recruitment and retention within the current wage band – would point to a target hourly wage of $25.00 per hour for a range of health and social service positions. Additional considerations should be discussed at an organizational level (e.g. whether the target represents an equivalent combination of salary and benefits, or a target for mid-point progression), but there is sufficient evidence to support this target as beneficial for both staff and services.

This target exceeds the estimated basic hourly living wage of $18.49 in Kelowna. While a living wage represents a strong base target that is useful for general discussion – especially in comparison to the minimum wage ($15.20 in BC as of June 1, 2021) and in the context of families – this higher sector target wage of $25 per hour better responds to the challenges associated with the existing pay range ($19.50-$24.50 per hour), the limitations of a living wage target (including debt, especially debt for professional education and training), and the cost of living regardless of family composition (recalling living wage calculations look at the needs of a family of four, and not necessarily individuals).

While the $25.00 mark has been identified in other contexts (see for-profit targets for Aspiration and Bank of America), this specific target should be adopted in accordance with the local evidence. While other jurisdictions should identify sector wage targets based on their respective context, this likely represents an appropriate wage target in other regions facing housing challenges. This was further evidenced during the recent election campaign with the pledge to raise the minimum wage of personal support workers to $25.00 (The Canadian Press / Global News, August 2021).

Actioning a $25.00 target wage will require discussion and shared acceptance of the premise that more is needed, as well as coordinated action moving forward in adopting this target. We encourage local agencies to cite this document and the associated sources in grant applications moving forward to justify a move towards a $25.00 wage across the sector. Likewise, we encourage regional, provincial, and federal funders to accept this target in light of the presented evidence.

Shared adoption of a target wage equivalent to cost of living (and above the base minimum needed to survive) will facilitate stability such that subsequent action can be taken to address other identified needs, including addition training and a broadening of support systems for staff and clients alike.

|

The Kelowna Homelessness Research Collaborative (KHRC), is a multidisciplinary team of researchers interested in understanding and supporting the provision of services to – and the perspectives of – individuals with lived experience of homelessness or who are vulnerable to homelessness. Investigators and collaborators are primarily based in the Okanagan Valley of British Columbia, Canada. Given the strength of the evidence presented above, the Kelowna Homelessness Research Collaborative will similarly shift our practices in support of a target hourly wage of $25, and work to embed that target into all future grant applications and collaborations. This will apply to research staff as well as research informants for all projects in which paid honoraria is appropriate. This is particularly relevant to work involving community members with Lived and Living Experience of homelessness, be they research informants and / or partnered Co-Researchers. |

Sources Referenced

- Levesque, J., Sehn, C., Babando, J., Ecker, J., & Embleton, L. (August 2021). Understanding the Needs of Workers in the Homelessness Support Sector. Hub Solutions. https://www.homelesshub.ca/sites/default/files/attachments/HubSolutions-Understanding-Needs-Oct2021.pdf

- Schiff, J. W., & Lane, A. M. (2019). PTSD symptoms, vicarious traumatization, and burnout in front line workers in the homeless sector. Community Mental Health Journal, 55(3), 454-462. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s10597-018-00364-7

- Jeffrey, A. (March 2019). Homeless shelter workers across Alberta struggling with post-traumatic stress disorder, study finds. Toronto Star. https://www.thestar.com/calgary/2019/03/27/homeless-shelter-workers-across-alberta-struggling-with-post-traumatic-stress-disorder-study-finds.html

- Poskitt, M. (July 2019). Emergency Shelters: Staff Training, Retention, and Burnout. Housing Research Collaborative. https://housingresearchcollaborative.scarp.ubc.ca/files/2019/07/Emergency-Shelters-Staff-2019PLAN530-HSABC.pdf

- Schiff, J. W. & Lane, A. (2016). Burnout and PTSD in Workers in the Homeless Sector in Edmonton. https://www.homelesshub.ca/sites/default/files/attachments/PTSD%20and%20Burnout%20in%20Edmonton%20February%202016.pdf

- Castle, N. G., & Engberg, J. (2005). Staff Turnover and Quality of Care in Nursing Homes. Medical Care, 43(6), 616–626. http://www.jstor.org/stable/3768180

- Antwi, Y. A., & Bowblis, J. R. (2018). The impact of nurse turnover on quality of care and mortality in nursing homes: Evidence from the great recession. American Journal of Health Economics, 4(2), 131-163. https://www.econstor.eu/bitstream/10419/172211/1/16-249.pdf

- Hussein, S. (2017). The English social care workforce: the vexed question of low wages and stress. In: Christensen, Karen and Pilling, Doria, eds. The Routledge Handbook of Social Care Work Around the World. Taylor & Francis, 74-87. https://kar.kent.ac.uk/68295/1/Routledge-17-AcceptedChapter.pdf

- Barnett, W. S. (2016). Low Wages = Low Quality: Solving the Real Preschool Teacher Crisis. National Institute for Early Education Research. https://nieer.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/08/3-1.pdf

- Ivanova, I. & Saugstad, L. (May 2019). Working for a Living Wage: Making Paid Work Meet Basic Family Needs in Metro Vancouver (2019 Update). Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives. https://www.policyalternatives.ca/sites/default/files/uploads/publications/BC%20Office/2019/05/BC_LivingWage2019_final.pdf

- Living Wage for Families BC. Living Wage Rates 2021 – Living Wages Rise Across BC. https://www.livingwageforfamilies.ca/living_wage2021

- Ivanova, I., Knowles, T., & French, A. (2021). Working for a Living Wage: Making Paid Work Meet Basic Family Needs in Metro Vancouver (2021 Update). https://d3n8a8pro7vhmx.cloudfront.net/livingwageforfamilies/pages/468/attachments/original/1635810616/Living_Wage_report_2021.pdf?1635810616

- Toor, K. (September 2019). A profile of workers in the homelessness support sector. Statistics Canada. https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/pub/75f0002m/75f0002m2019010-eng.htm

- Community Social Services Employers’ Association of BC. (April 2021). Wage Grids – By Grid Level. https://www.cssea.bc.ca/PDFs/JJEP/April12021_WageGrids.pdf

- Urban Matters CCC. (July 2021). Complex Needs Advocacy Paper. City of Kelowna. https://www.kelowna.ca/sites/files/1/docs/community/Journey-Home/2021-7-12_complex_needs_advocacy_paper.pdf

- Living Wage Canada. (n.d.). Calculating a Living Wage. http://livingwagecanada.ca/index.php/about-living-wage/calculating-living-wage-your-community/

- Slotnik, D. E. (April 2021). She Works in a Homeless Shelter, and She Lives in One, Too. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2021/04/16/nyregion/shelter-workers-homelessness.html

- CitySpaces Consulting Ltd. (November 2019). Regional Housing Needs Assessment: Regional District of Central Okanagan. Regional District of Central Okanagan. https://www.rdco.com/en/business-and-land-use/resources/Documents/Regional-Growth-Housing-Needs-Assessment.pdf

- Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation. (n.d.). Identifying core housing need. https://www.cmhc-schl.gc.ca/en/professionals/housing-markets-data-and-research/housing-research/core-housing-need/identifying-core-housing-need

- Schwan, K., Vaccaro, M. E., Reid, L., Ali, N., & Baig, K. (September 2021). The Pan-Canadian Women’s Housing & Homelessness Survey. Toronto, ON: Canadian Observatory on Homelessness. https://womenshomelessness.ca/wp-content/uploads/EN-Pan-Canadian-Womens-Housing-Homelessness-Survey-FINAL-28-Sept-2021.pdf

- Nianias, H. (February 2016). As Rental Prices Rise, Women Stay in Bad Relationships to Survive. Vice News. https://www.vice.com/en/article/4xkzxq/as-rental-prices-rise-women-stay-in-bad-relationships-to-survive

- BC Housing. (n.d.). BC COVID-19 Temporary Pandemic Pay. https://www.bchousing.org/COVID-19-pandemic-pay

- Galanis, P., Vraka, I., Fragkou, D., Bilali, A., & Kaitelidou, D. (2021). Nurses’ burnout and associated risk factors during the COVID‐19 pandemic: A systematic review and meta‐analysis. Journal of Advanced Nursing. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/jan.14839

- Mental Health Commission of Canada. (July 2021). COVID-19, Mental Wellness, and the Homelessness Workforce: Policy Brief. https://www.mentalhealthcommission.ca/wp-content/uploads/drupal/2021-07/covid_mental_wellness_homelessness_workforce_eng.pdf

- Government of British Columbia. (n.d.). Minimum Wage. https://www2.gov.bc.ca/gov/content/employment-business/employment-standards-advice/employment-standards/wages/minimum-wage

- Cherny, A. (June 2021). Why I raised my company’s minimum wage to $25 an hour. Fortune. https://fortune.com/2021/06/11/minimum-wage-25-an-hour-aspiration-ceo/

- Brooks, K. J. (May 2021). Bank of America boosting its hourly minimum wage to $25 by 2025. CBS News. https://www.cbsnews.com/news/bank-of-america-minimum-wage-25-dollars/

- The Canadian Press. (August 2021). Trudeau promising to hire more PSWs with increased pay if re-elected. Global News. https://globalnews.ca/news/8125602/trudeau-promise-psw-increased-pay/